|

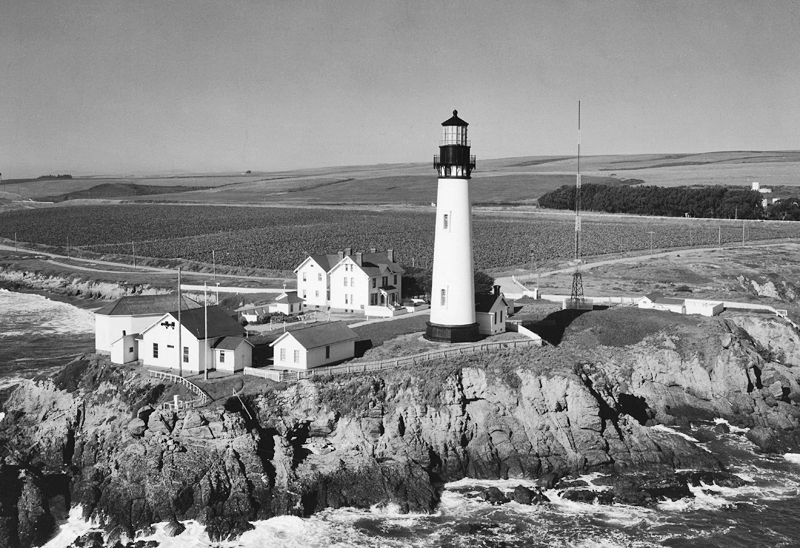

| Aerial view of Pigeon Point Lighthouse in 1959 Photograph courtesy U.S. Coast Guard |

After a struggle to secure property at the point, Congress appropriated a sum of $90,000 in March 1871 for a first-class lighthouse and fog signal on Pigeon Point. The fog signal and Victorian fourplex were completed first, and the twelve-inch steam whistle, with four-second blasts separated alternately by seven and forty-five seconds, was fired up for the first time on September 10, 1871. Torrential rains and difficulty in assembling the spiral staircase, which had been fabricated by Nutting & Son in San Francisco, contributed to delays in completing the tower. After the lantern room was in place atop the tower, the delicate lens was assembled inside, and the light was exhibited for the first time on November 15, 1872, over fourteen months after the fog signal was completed. At sunset that evening, Keeper J. W. Patterson started the brass clockwork ticking, ignited the lard oil in the lamp, and soon the lighthouse according to Patterson was “exchanging winks and blinks with its neighbor of the Farallones.”

Pigeon Point’s 115-foot tower shares the title of tallest west coast lighthouse with California’s Point Arena Lighthouse, and is similar in design to those at Bodie Island and Currituck Beach in North Carolina, Morris Island in South Carolina, and Yaquina Head in Oregon, though the heights of the towers differ. The first-order Fresnel lens used in Pigeon Point Lighthouse was manufactured in Paris by the firm of Henry Lepaute and is made of 1,008 separate prisms. Revolving at a rate of one revolution every four minutes, the lens’ twenty-four flash panels produced a characteristic of one flash every ten seconds. The pedestal that supports the jewel-like lens and the clockwork mechanism that revolve it were not introduced to lighthouse service at Pigeon Point. They first served in Cape Hatteras Lighthouse (an older tower, not the current one) until they were removed from that tower, placed in storage at the General Lighthouse Depot on Staten Island for a few months, and then shipped to Pigeon Point on August 11, 1871. The small building attached to the base of the tower contains an office on one side and an oil storage room on the opposite side of the central hallway. In 1909, a separate oil house, which now contains informational displays, was built away from the tower as a safety measure for storing the volatile kerosene fuel that was introduced as the illuminant in 1888 in place of lard oil.

A new boiler was installed in the fog signal building in 1881, and to protect it from “some substance destructive to boiler-shells and tubes” that was found in the water obtained from the station’s spring, the construction of a water collection basin and cistern was ordered. Two 4,500-gallon tanks were put up near the fog signal buildings, and a water shed with an area of 20,000 square feet was laid in the station’s nine-acre lot to collect rainwater. A new fog signal house, the one that remains standing today, was completed in 1900.

Besides looking after the light and fog signal, keepers at Pigeon Point also served as tour guides several days a week for visitors who came to get a look at the lighthouse. At least one keeper found some entertainment in this distraction as evidenced by a reporter’s account of his visit to the station recorded in an 1883 edition of the San Mateo County Gazette. “Our escort was of a very talkative disposition and took great pride in dilating upon the wonders of the establishment. As we stood inside the immense lens which surrounds the lamp, he startled us by stating in impressive tones that, were he to draw the curtains from the glass, the heat would be so great that the glass would melt instantly, and that human flesh would follow suit; we begged him not to experiment just then, and he kindly refrained.”

As the original quarters were rather confining for the station’s four keepers and their families, a large addition was completed in 1906 to provide four additional living rooms and four bathrooms. One can only imagine that the mothers at Pigeon Point and other lighthouses were always anxious regarding the safety of their children, whose yards were so close to the ocean. In October 1878, one mother’s heart was broken when five-year-old Stewart Munroe, son of Assistant Keeper John Munroe, fell over the bluff and into the sea while playing with another child near the lighthouse. Only the child’s hat was immediately found, and the distraught parents offered a reward to anyone who recovered the body.

Jesse Mygrants requested a transfer from Point Arguello to a station where his daughters could attend school. The Lighthouse Service complied and assigned him to Pigeon Point in October 1924. One of these daughters, Jessie, recalls her father helping her with homework at a small desk in the watchroom as the giant lens slowly rotated just overhead.

In the spring of 1933, Mygrants and the other keepers were using blowtorches to remove old paint from the exterior of the Victorian dwelling when Jesse noticed that one of the nails in the dwelling remained hot long after the removal of the blowtorch. Putting his ear to the wall, he alarmingly heard the crackle of fire. Smoke soon started to issue from the dwelling, and its many occupants began scurrying to remove their prized possessions. The keepers bravely fought the fire until a fire truck summoned from Redwood City reached the station in a record forty-five minutes – a mighty fine time even with today’s improved roads. The damage from the fire was limited to the eastern side of the dwelling, that used by the Mygrants, and though they were inconvenienced for some time, a crew of workers patched up their apartment during the summer.

|

In 1960, the original fourplex, though still in good condition, was razed, and four ranch-style houses were built by the Coast Guard, in what one must admit now was clearly an aesthetic compromise. A rotating aero-beacon was placed on the balcony outside the lantern room in 1972, and the Fresnel lens was deactivated. This move, allowed the station to be automated in 1974. Pigeon Point Lighthouse was added to the National Regsiter of Historic Places in 1977. In 1980, the four generic houses were leased to American Youth Hostels, Inc., for use as economical, dormitory-style accommodations.

In 2000, just as the Lighthouse Inn, a bed and breakfast located adjacent to the lighthouse property, was nearing completion, the Peninsula Open Space Trust purchased the inn and surrounding property. The inn was promptly dismantled, and the property returned to a natural state. Thanks to this “undevelopment” project and other purchases by the trust, the area around Pigeon Point Lighthouse should remain in a natural state for years to come.

Two large sections of a brick and iron cornice located high atop the tower fell to the ground in December 2001, prompting the closure of the tower and the area immediately around its base. The following year, the lighthouse was listed for transfer under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act. California State Parks and Peninsula Open Space Trust filed a joint application for ownership of the lighthouse and received the National Park Service’s recommendation in 2004. Two non-profits appealed the decision, but Pigeon Point Lighthouse was officially transferred to the state in May 2005. The California State Parks Foundation spearheaded a multi-million-dollar fundraising campaign, in partnership with State Parks and the San Mateo Natural History Association, to restore and reopen the historic Pigeon Point Lighthouse.

In the summer of 2011, California State Parks announced that thanks to a $175,000 grant from the Hind Foundation the first phase of restoring Pigeon Point Lighthouse would begin later that fall. The first-order Fresnel lens was disassembled and removed from the lantern room on November 12 and 13, and then cleaned and reassembled in the fog signal building, where it is now on display for the public. The $325,000 first phase of the restoration also included coating iron on the tower with rust inhibitor, repairing broken windows, and some other repair work.

In May 2012, the California Coastal Conservancy provided $200,000 so plans could be drawn up for a detailed restoration of the lighthouse, which was estimated to cost $7 million. The State Parks Foundation ended its fundraising campaign in 2019 after having raised $3 million. The California legislature appropriated $9.2 million for Pigeon Point Lighthouse in 2019, but that money was later redirected. The 2021 state budget included $18.9 million for a thorough restoration of the lighthouse, and in 2022, plans were finalized and bid documents were prepared.

In December 2023, California State Parks announced that a contract for a $16 million rehabilitation of Pigeon Point Lighthouse had been awarded to Sustainable Group, Inc. of Moraga, California with ICC Commonwealth of North Tonawanda, New York as a major subcontractor. These two companies have jointly worked on nearly 100 lighthouses including Bodie Island Lighthouse and Currituck Beach Lighthouse that are quite similar to Pigeon Point Lighthouse. The restoration work started in early 2024 and is expected to be completed in 2026.

The popular annual lighting of the Fresnel lens will be interrupted for several years, but California State Parks promised the lens would be returned to the lantern room in the future.

Keepers:

References